Using Opendrift source code and data of wave, wind and current data from 1983 downloaded from https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=overview (10m wind and waves) and https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-oras5?tab=overview (currents 0.5m) the debris drift can be modelled for the first few days.

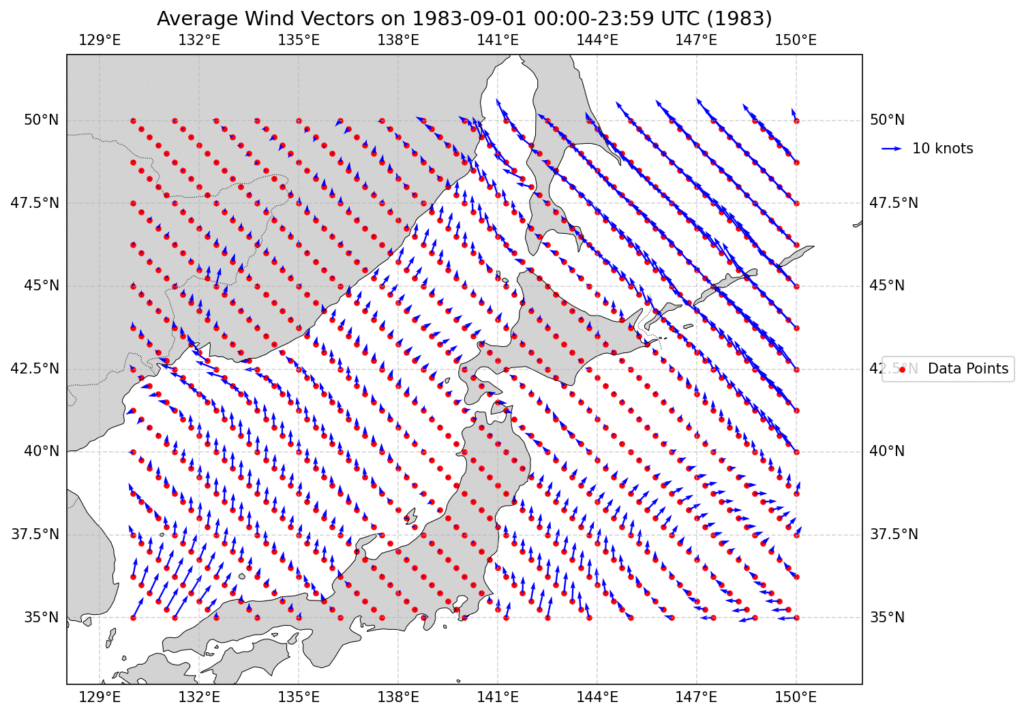

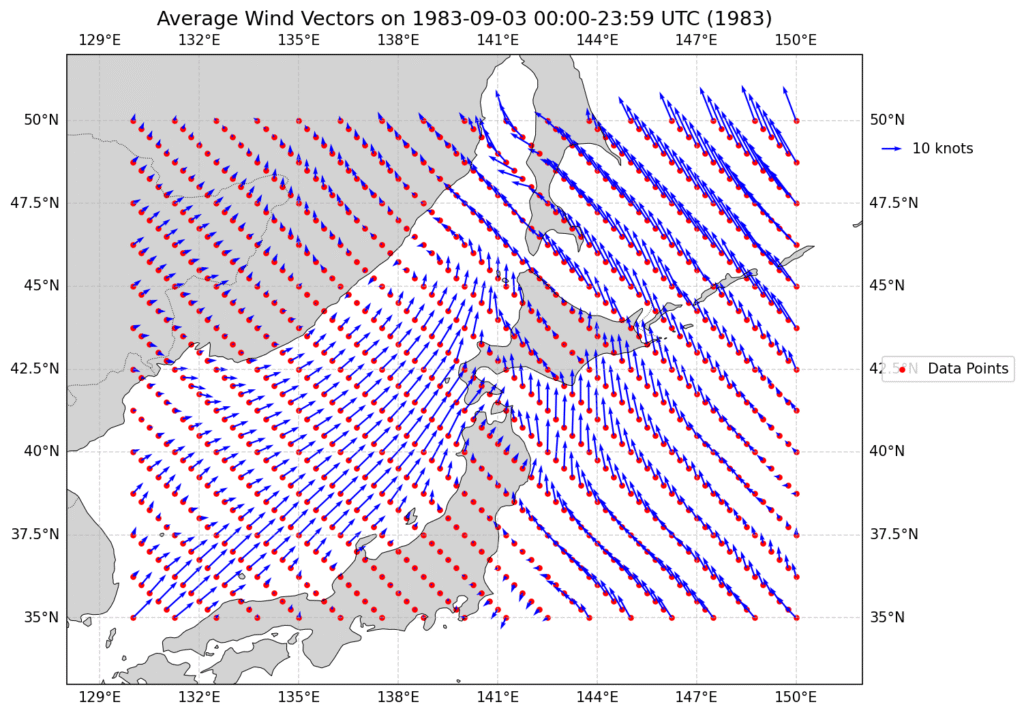

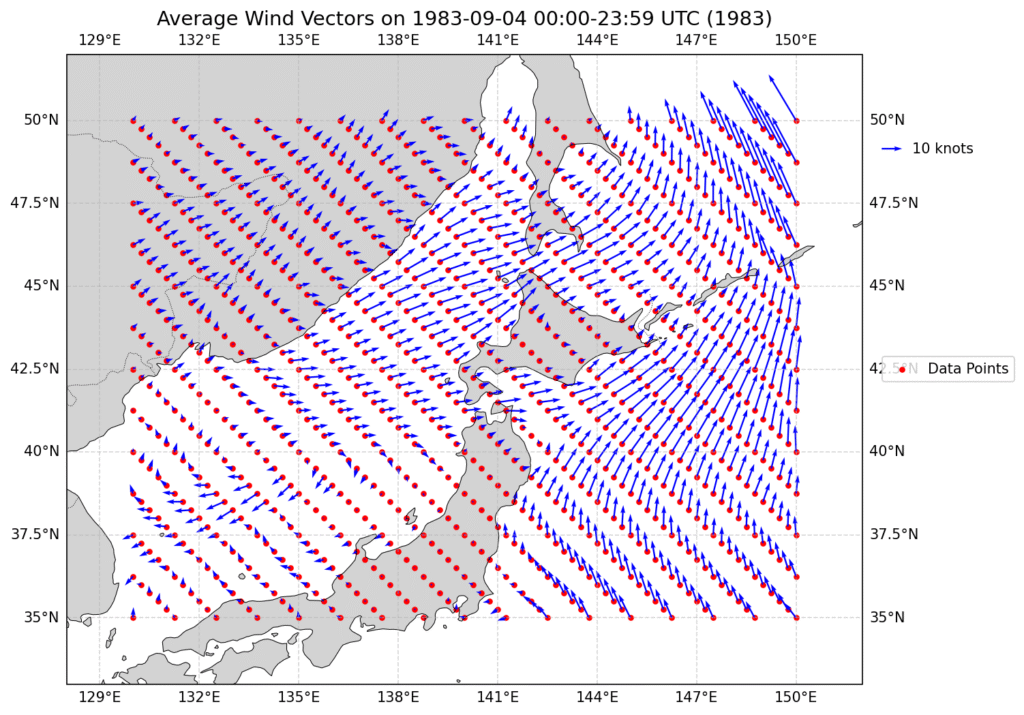

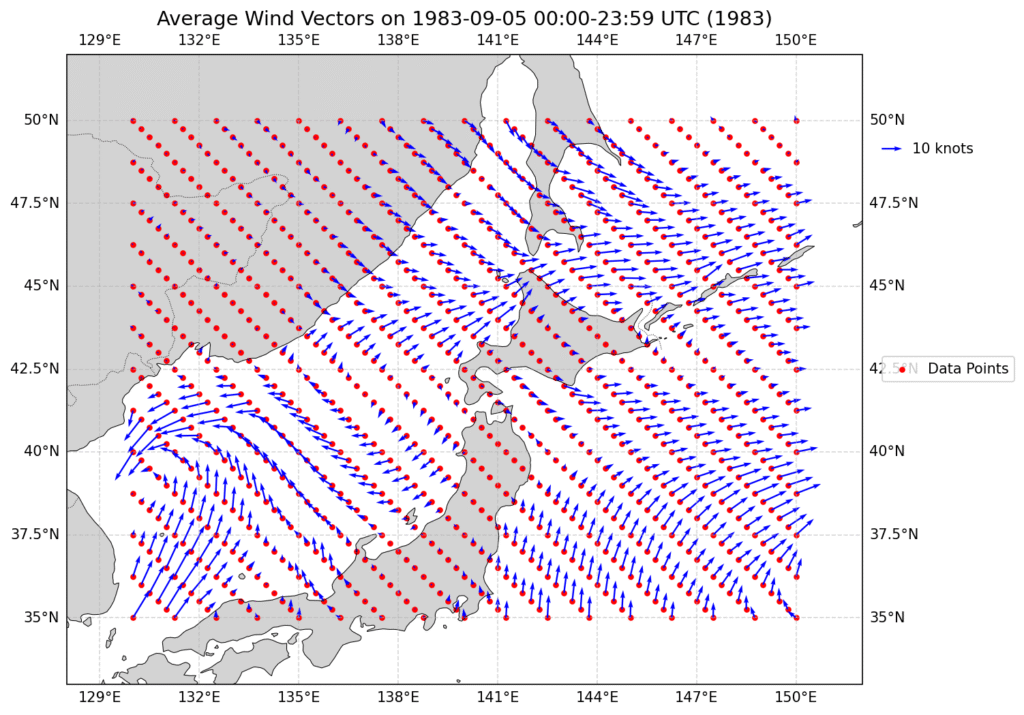

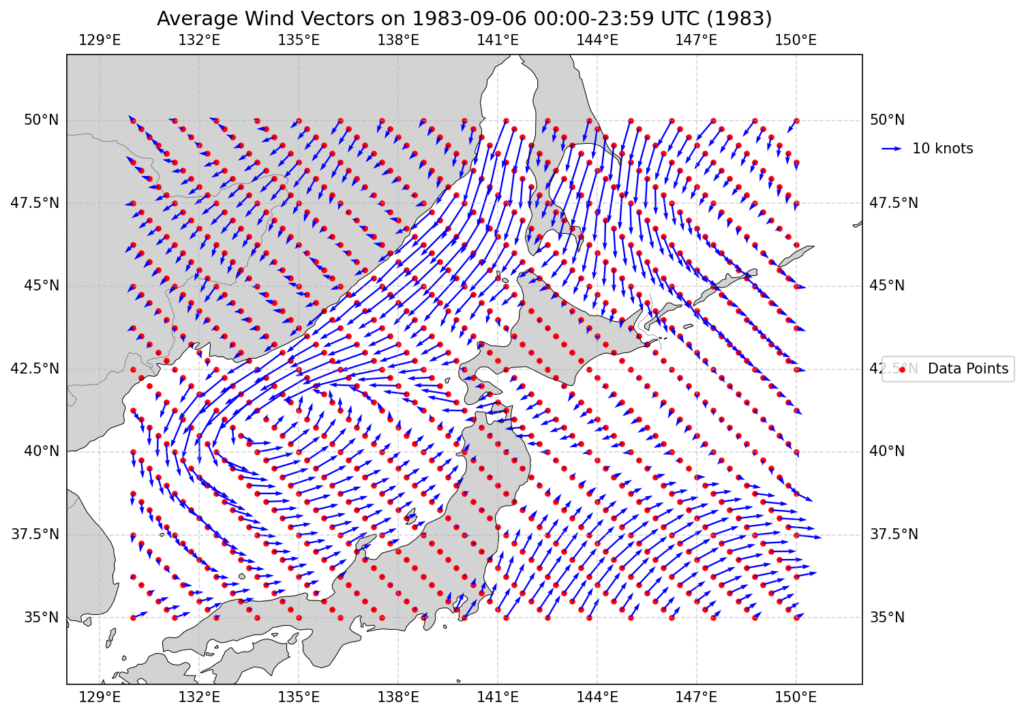

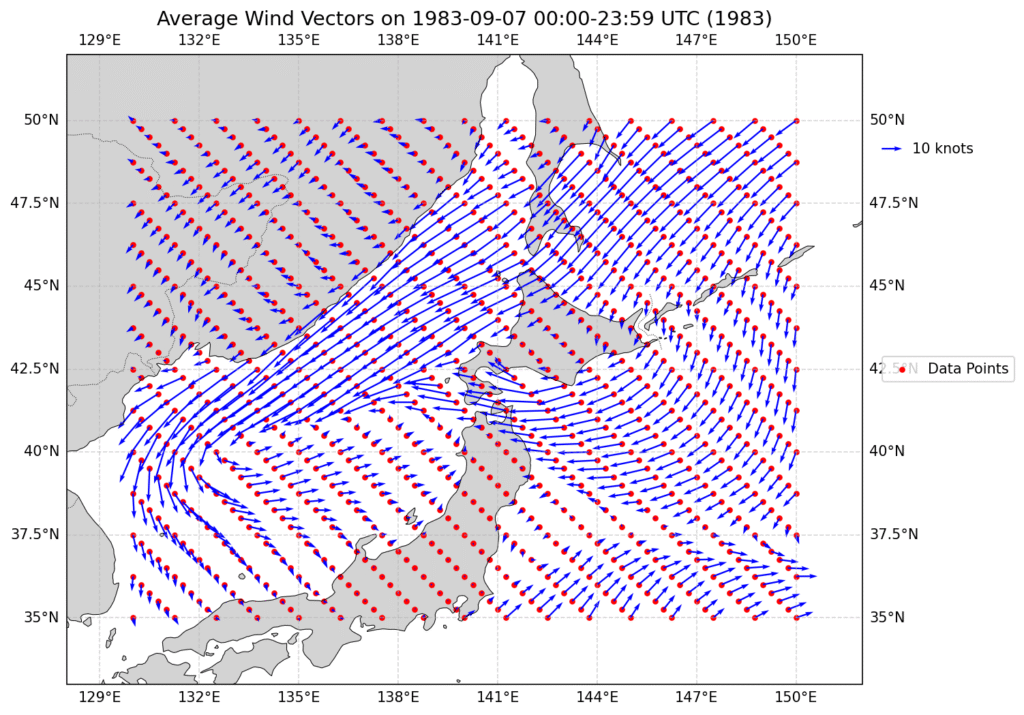

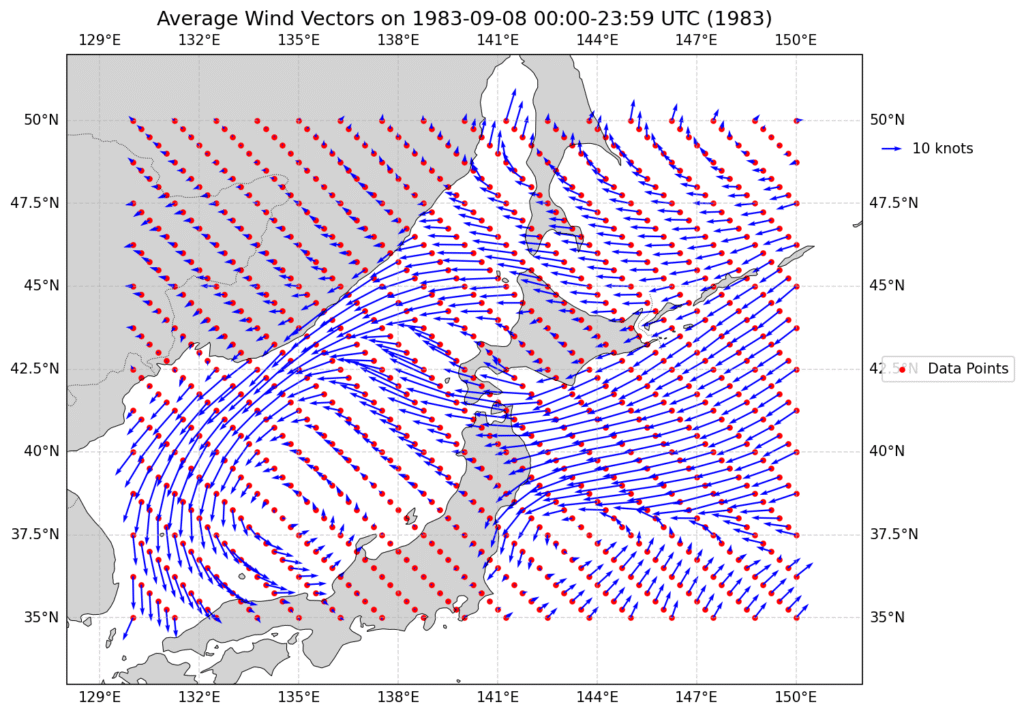

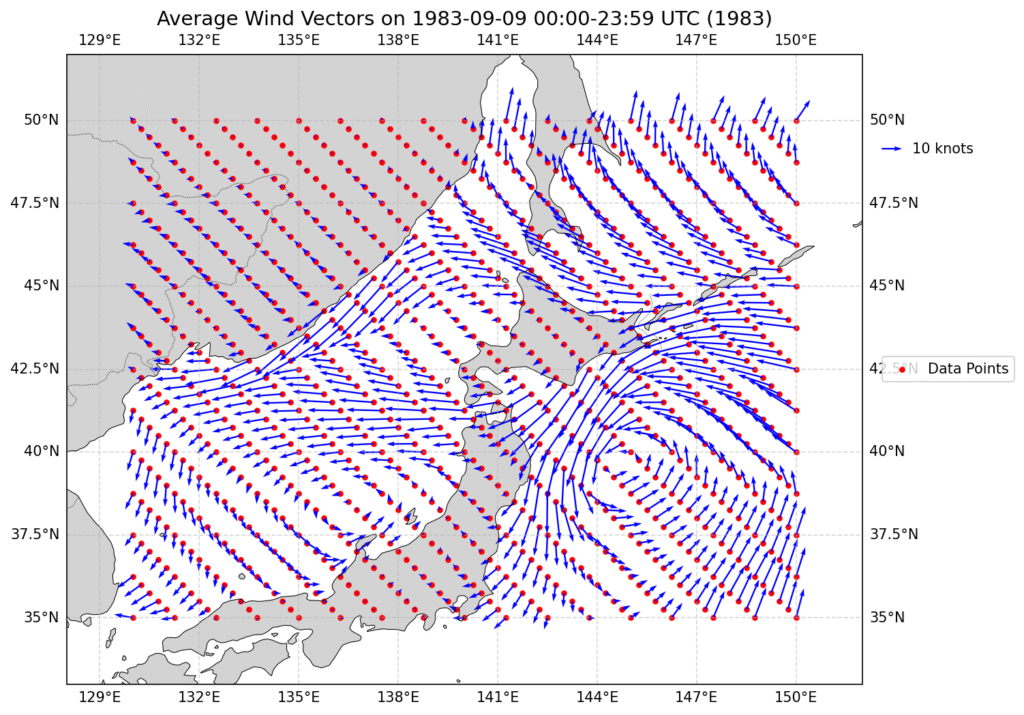

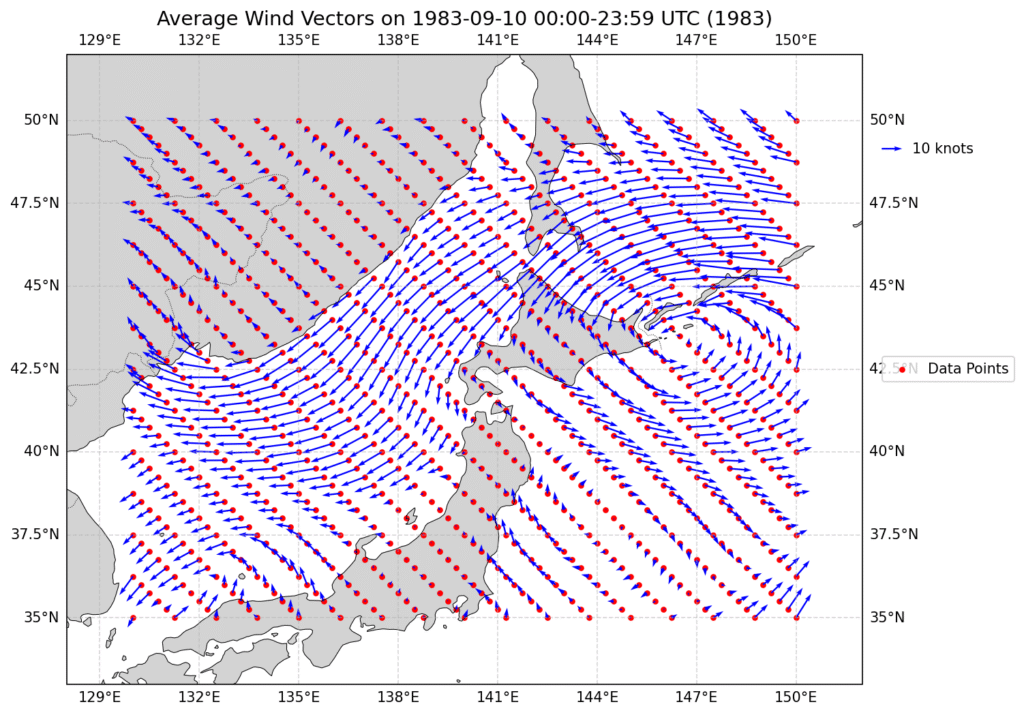

The daily winds for the first 10 days are shown below with the first 2 days essentially calm in most locations. The wind then turns into a strong breeze in the NE direction for 2 days before swinging strongly in the opposite direction. Sept 10 is when the first pieces of debris were seen on Northern Hokkaido.

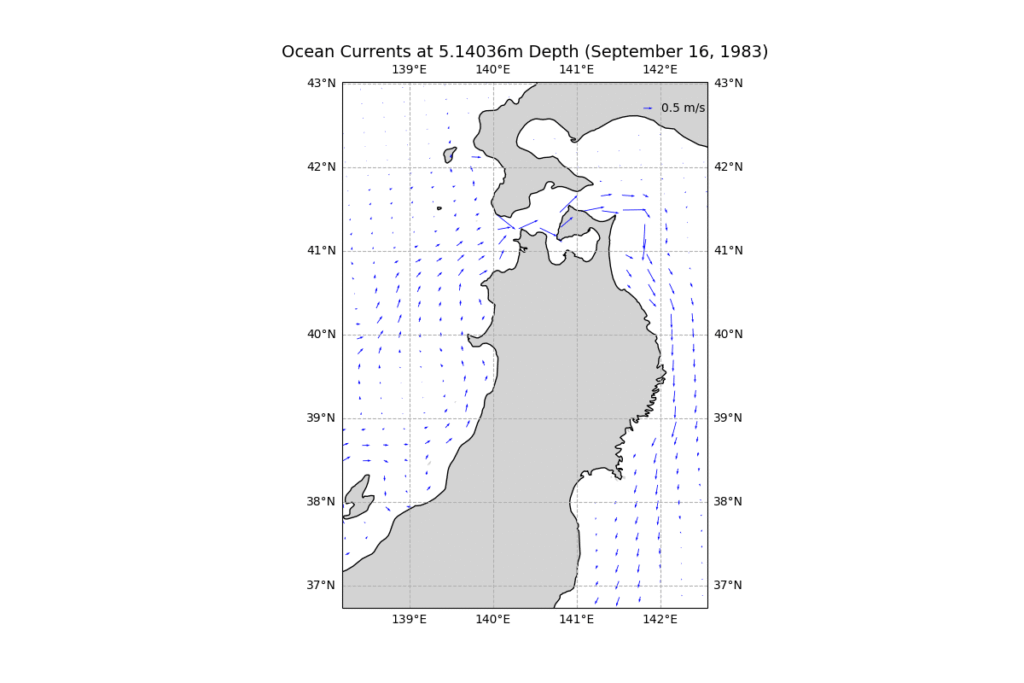

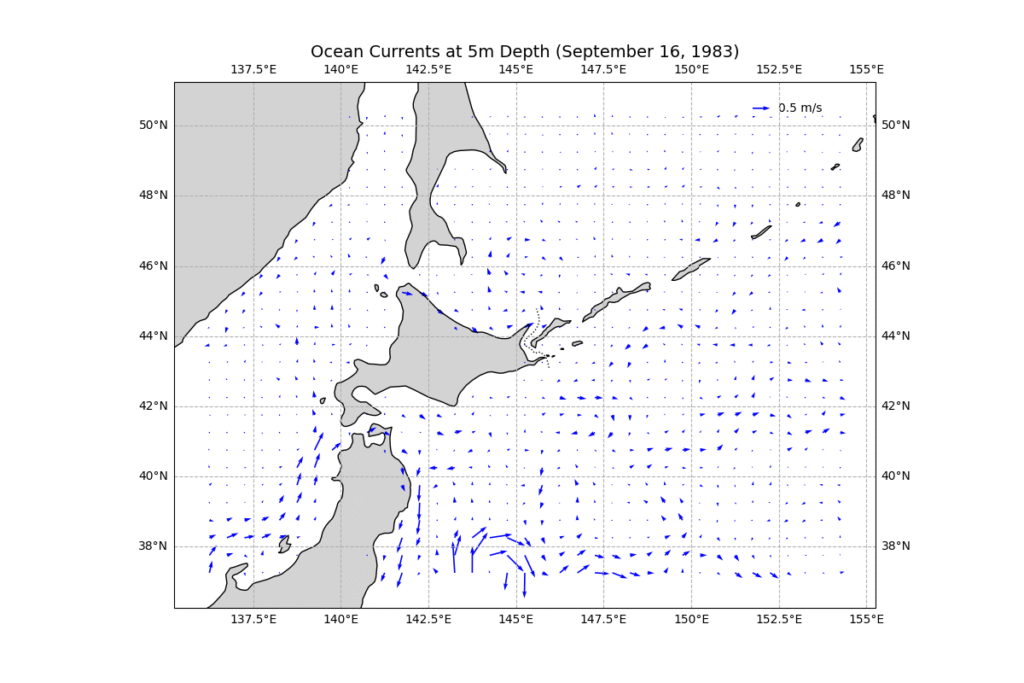

The current data at 0.5m is average monthly shown below but is always in a NE direction between 1.5kts to 7.5kts. Note the currents are monthly averages reported Aug 16th and Sept16…there is almost no change between the Aug and Sept currents but they were interpolated for the modelling. Also note there is very little northerly current on the west side of Hokkaido.

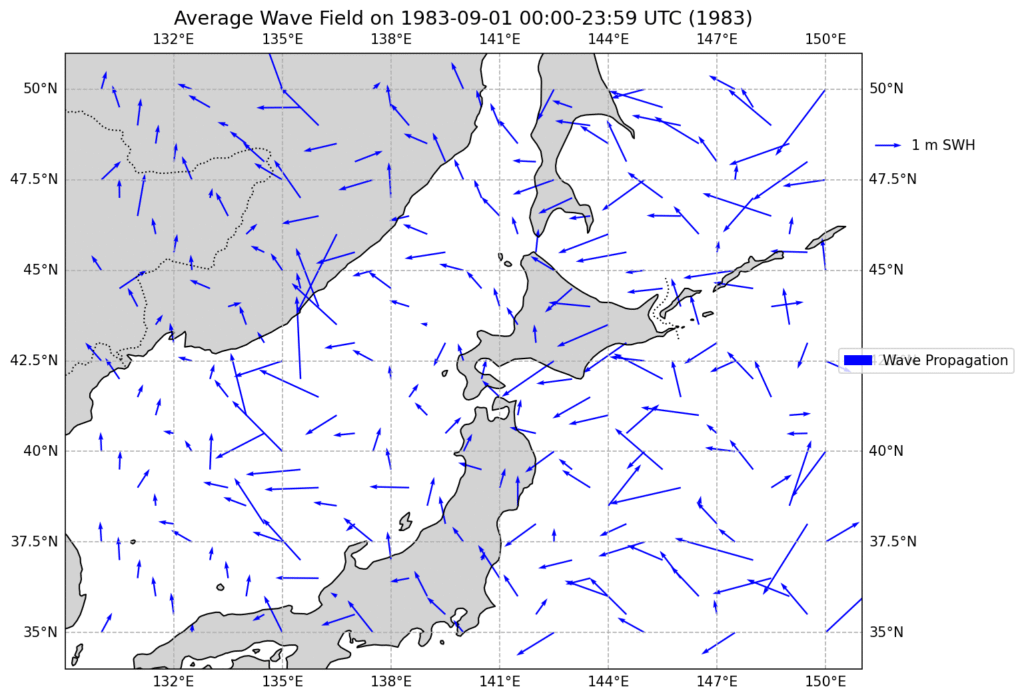

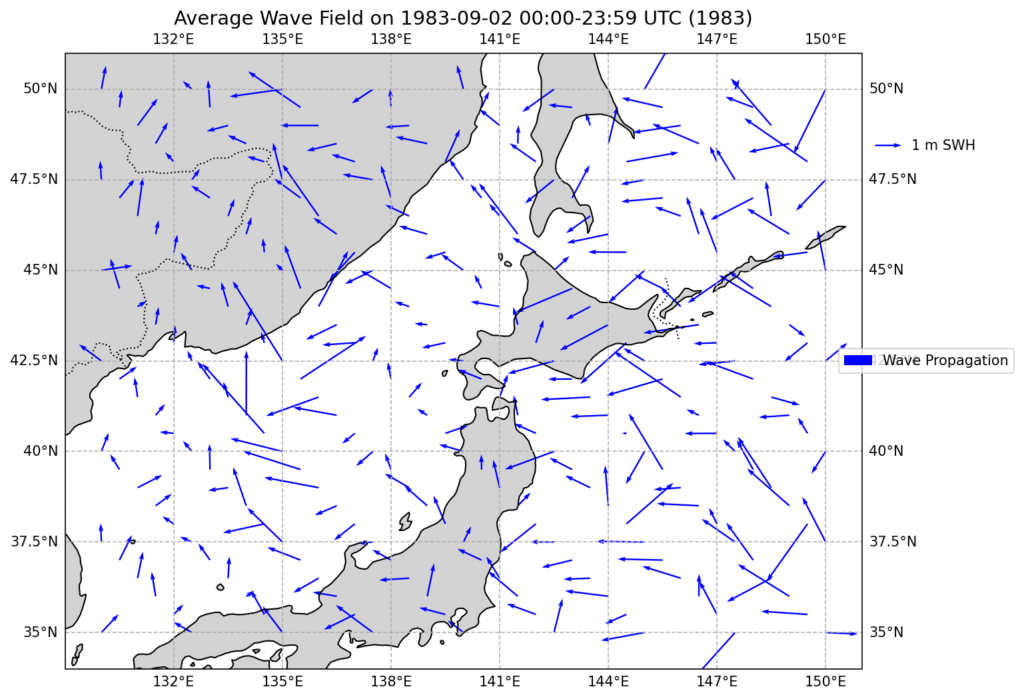

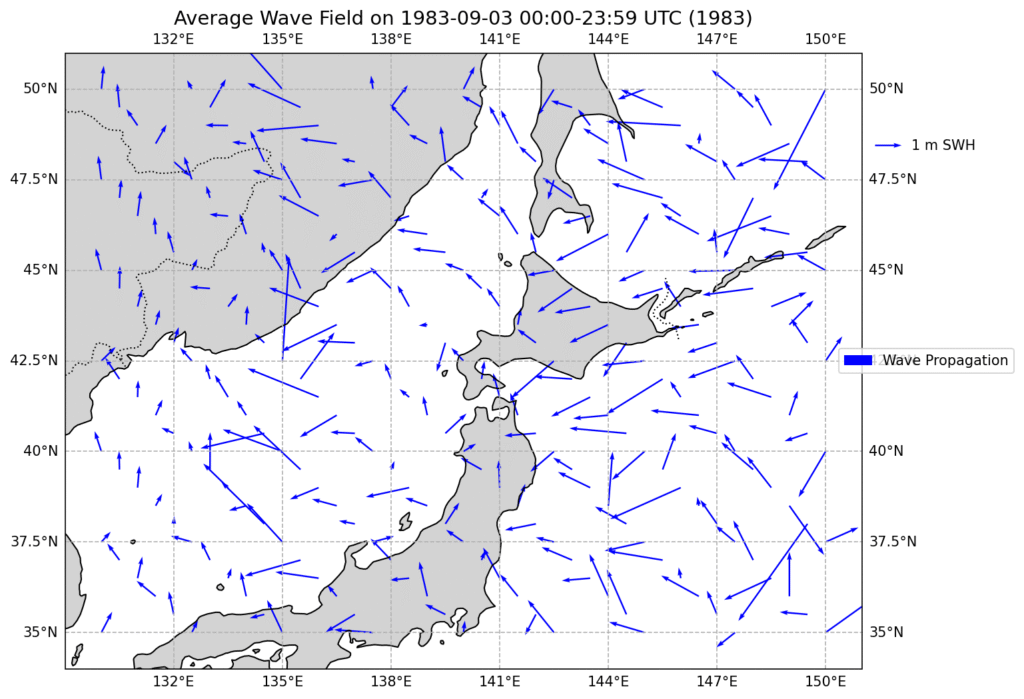

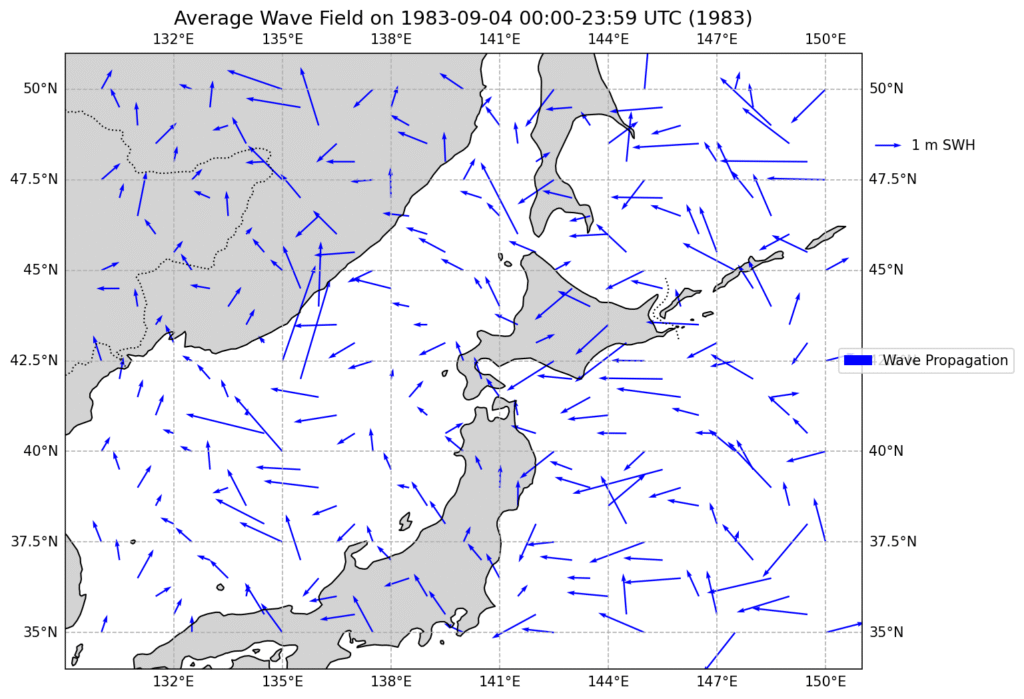

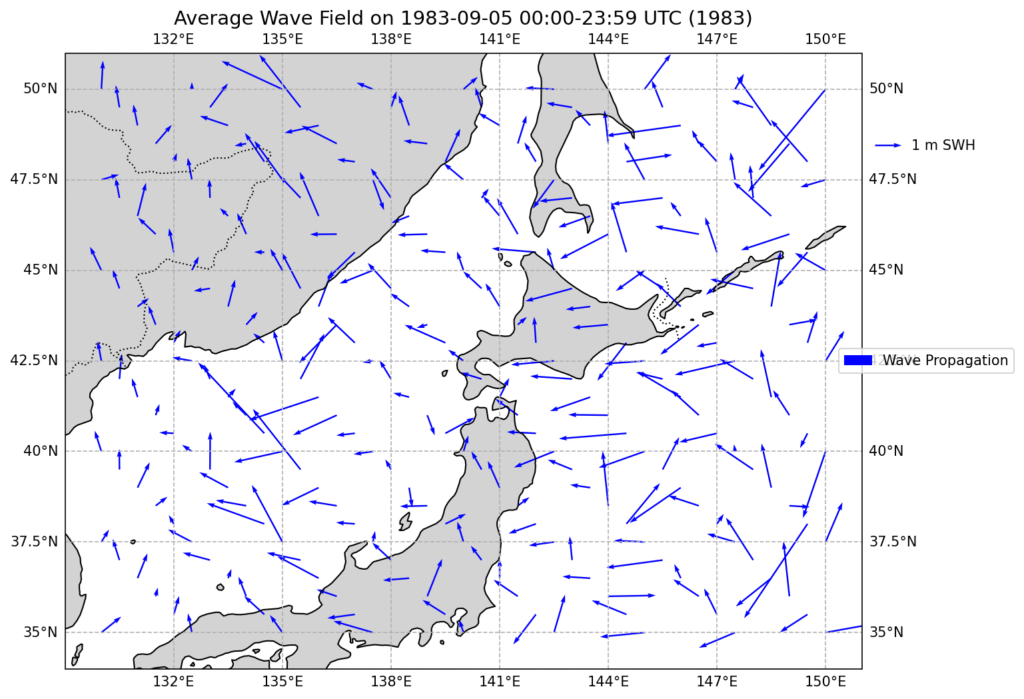

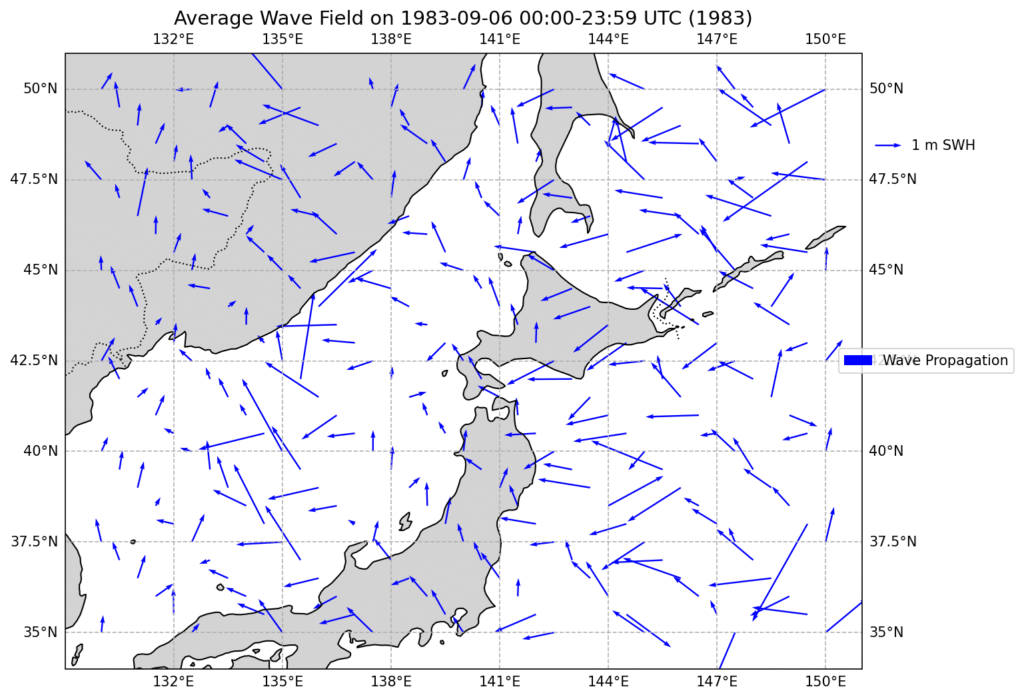

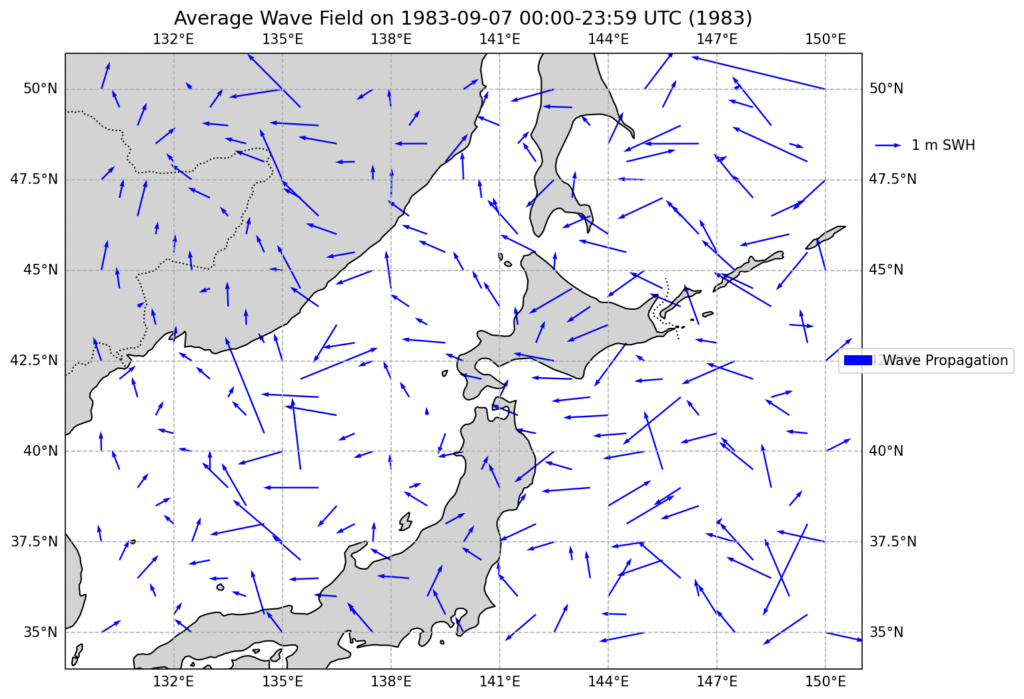

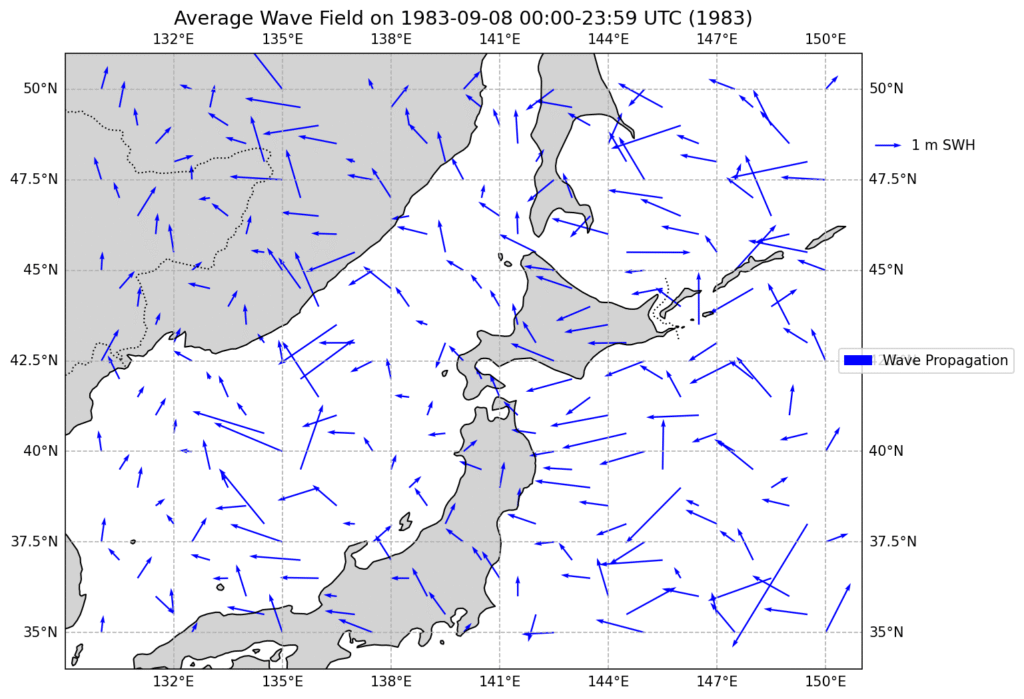

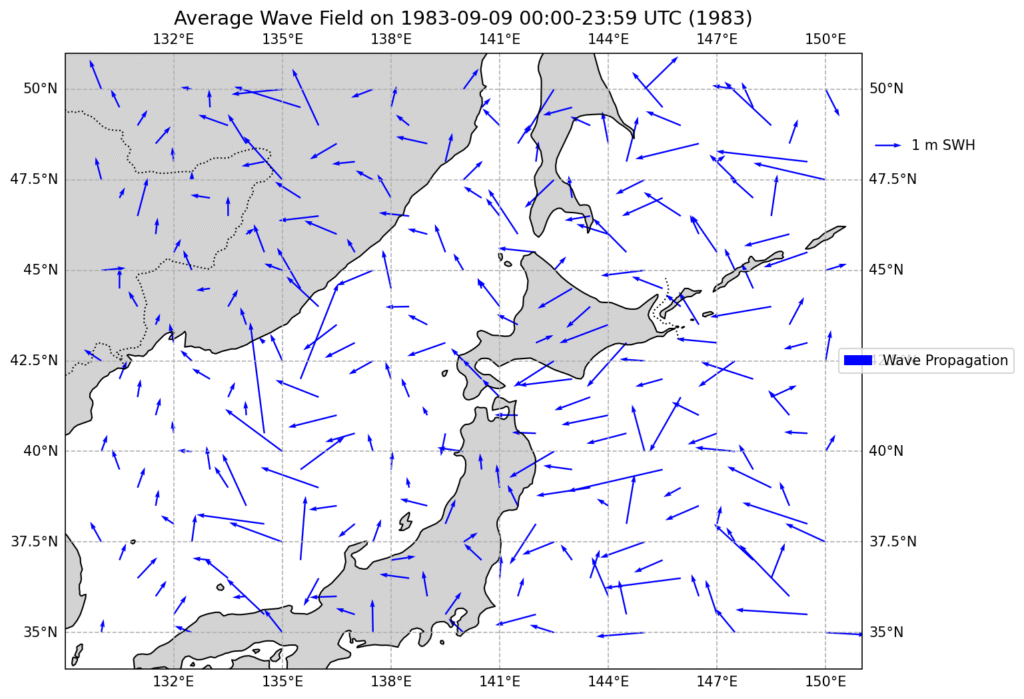

The effect of waves on the debris is accounted for using Stokes in the modelling which were main SE. The first 9 days of the wind is shown below.

Experimentally, by using real Amaride Honeycomb debris from KAL007 and a simple pool experiment (below) an L value of 0.07 was obtained. In other words, for a 10 knot wind the debris would move at 10 * 0.07 or 0.7knots from the wind. This was remarkably steady over a range of different wind velocities tested. Other debris (solid Aluminium/plastic sandwich) just floated and gave L values of 0.02.

The first simulation (click below image to run) was run using the official crash location. I used an initial dispersion of 6kmx6km based on Lockerbie debris field. It speaks for itself that this cannot be the real crash location as the debris remains relatively in the same area or mostly ends up on Sakhalin shores. There were at least 80 ships and numerous aircraft in this area over the first few weeks and none of them found any debris for at least 8 days. The small amount that did arrive on northern Hokkaido is all only just floating (low L values). This is opposite what was collected. Much of the Hokkaido debris was the honeycomb composite material.

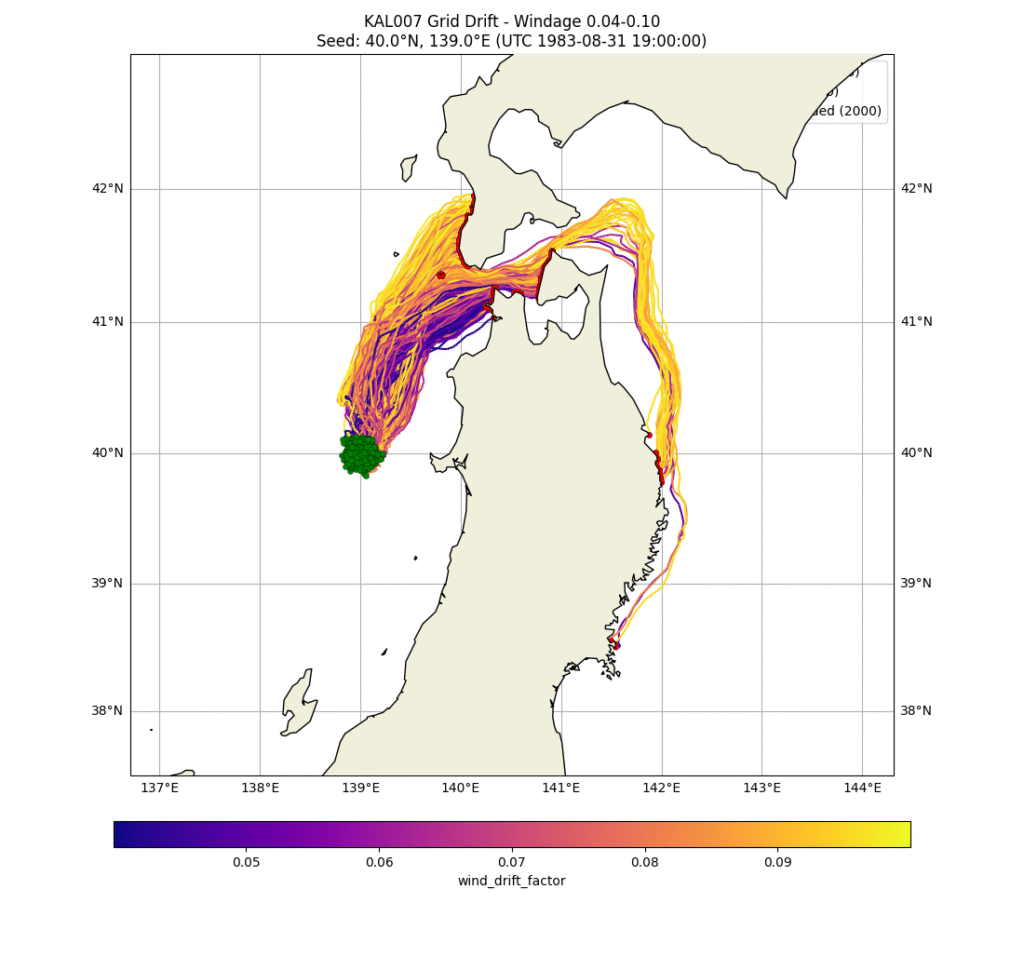

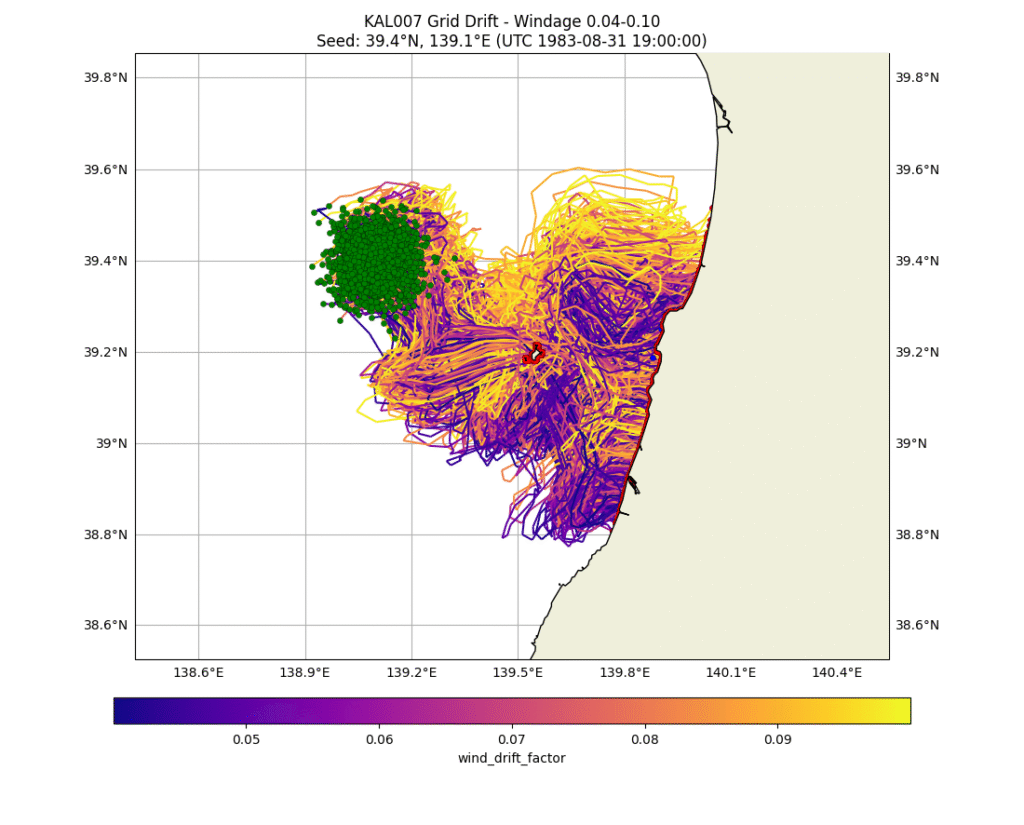

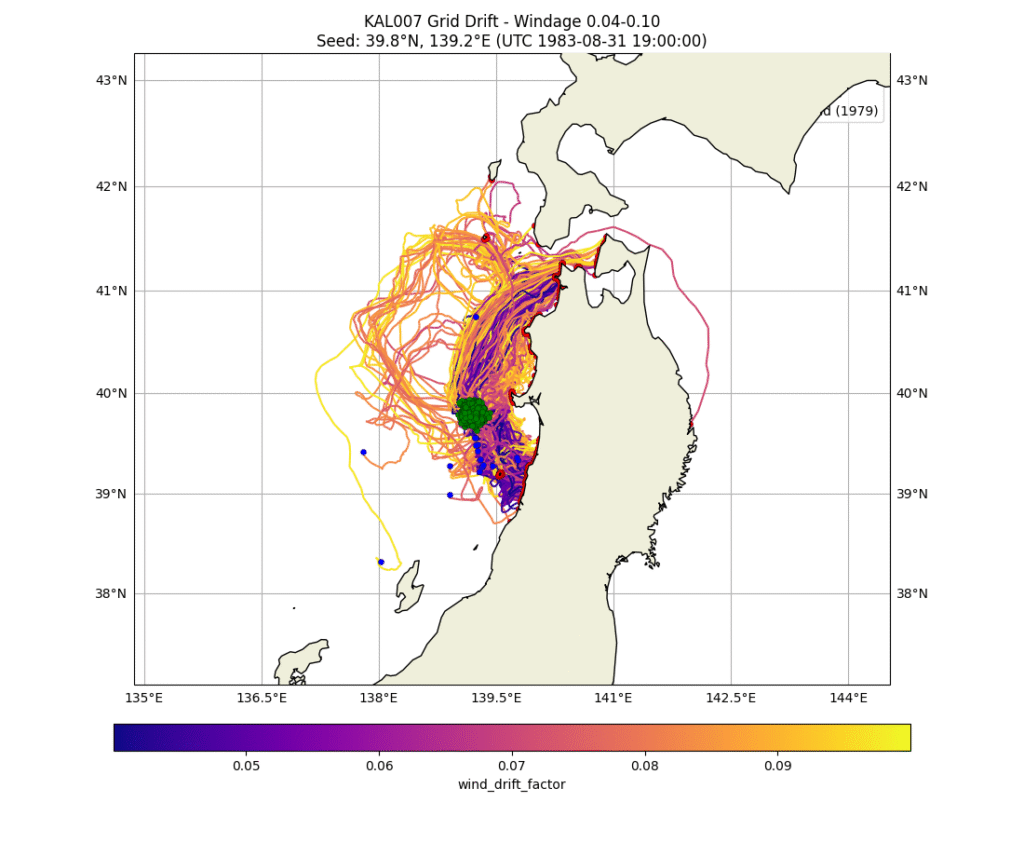

Running the model over many potential starting locations reveals only a single location that can both get debris through the Tsugaru Strait and get close to Chasu beach by the 6th Sept as well as debris to arrive on beaches south of Akita. Moving the start location just 0.1 deg in any direction either make the debris not travel south or not through the Tsugaru strait quickly enough. Whilst this model is fairly basic and doesn’t account for eddies etc it does show a possible crash location. I have requested ocean drift experts to check my drift but as yet have not had feedback.

Interestingly, the modelling shows that it is simply impossible for debris to arrive north of Hokkaido at any time. This is due to strong NE wind (i.e. wind blowing towards the SW) after Sept 6th and little northerly current above the Tsugaru Strait. This strongly suggests the debris found in Sakhalin and Northern Hokkaido was purposely moved.

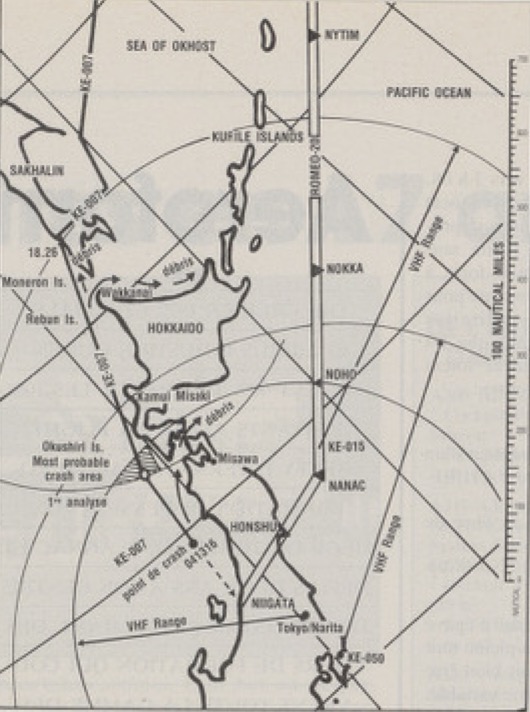

It is interesting to note that this is almost exactly the same location as Michel Brun determined independently from time analysis of KAL007’s last radio call’s. He published a map below (in Aviation magazine 15 Aug 1990) showing crash location 115NM north of Niigata at 04:13:15 local time.

I ran the simulation over a grid pattern of 0.1 deg roughly from the official crash location near Moneron all the way to Sado Island near Niigata covering all possible flight paths that KAL007 could have taken. As mentioned there is only one small spot covering 0.1 deg in each direction that debris travels both through the Tsugaru Strait and to the beaches south of Akita.

Some further modelling was done introducing some horizontal diffusivity and increasing the radius of seed points to 5km. This gave some results more closely matching observed debris. i.e. Particles got through the Tsugaru Strait to plausibly arrive at Chasu beach on the 5th Sept with particles also arriving at Okashiri Island and South of Akita. Any seed latitude greater (more northerly) than 39.9 deg resulted in no arrivals south of Akita. Similarly any latitude further south than 39.5 resulted in no particles reaching the Tsugaru Strait. This is a 50km window in the N/S direction. Similarly longitudes outside 138.4-139.2 range generated unrealistic results not matching observations.

Moving the seed point slightly west gets more debris arriving at Okashiri Island but particles don’t get through the Tsugaru strait. This may imply the debris field was relatively wide.

The modelling shows a lot of debris arriving at Cape Tappi at the entrance to the Tsugaru Strait but it is unlikely that this actually occurred as the current in this area is extremely swift (over 7knts) and travels parallel to the coast and thus swept into the Tsugaru Strait. See short video below of this steady constant current. Any debris that did wash up in this area would likely go unnoticed as it largely unpopulated and rugged.

There is some possibility that KAL007 came down closer to waypoint KADBO (39.236105N, 137.746791E) as Navy Foxtrot Bravo 650 arrived at that waypoint at 4:27 local time, about 14 minutes after KAL007 is believed to have been shot down and commenced a low level search. However my debris drift analysis suggests this is not the case as debris does not travel quickly enough through the Tsugaru strait as the animation below shows.

Debris drift modelling with seed longitudes between KADBO and the believed impact also show debris does not travel quickly enough through the Tsugaru strait in order to arrive at Chas beach by the morning of the 6th Sept.

In summary, the majority of debris from KAL007 travelled quickly through the Tsugaru strait and out into the Pacific Ocean. A small amount (20 pieces) arrived on the coast around Sai but was quickly discredited by the military as target drone wreckage. A single piece arrived at Chas beach. Some debris (most likely from the front of the aircraft) travelled south to the beaches south of Akita.

One may wonder how all the wreckage that arrived on the beaches south of Akita was not discovered at all at the time and remain in full sight to this day. The explanation is quite simple. The beaches are deserted and extremely sparsely populated. I have spent over 4 weeks walking the beaches on the west of Japan and have met one person during this time. The beaches are also incredibly littered by other flotsam. The debris simply just looks like every other bit of junk and is easily overlooked. The beaches are also typically wide and flat and an unusual large weather event just a few days after the incident generated large swells which would have pushed the debris well onshore, mixing with other junk. An example of a few typical beaches south of Akita is shown below.